|

| |||

| |||

| |||

The Persistent Puppet: Pinocchio's Heirs in Contemporary Fiction and Film

BY | Rebecca West

SESSION 1: The Value of PinocchioSESSION 2: Collodi: His Works and His Italy

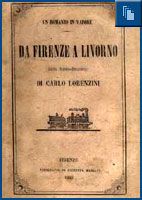

Editor's Note: To best appreciate this seminar, download a copy of Collodi's Pinocchio for your reference. "Once upon a time, there was ... 'A king!' my little readers will say right away. No, children, you are wrong. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood." Thus begins The Adventures of Pinocchio, starring a long-nosed puppet who is one of the world's most immediately recognizable characters since his creation more than a century ago by the Tuscan writer Carlo Lorenzini, known as Collodi.

Web Link View the trailer to Steven Spielberg's film A.I.: Artificial Intelligence. The latest references to Pinocchio are to be found in what seems at first to be an unlikely place: Steven Spielberg's 2001 film, A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, based on Stanley Kubrick's project that was cut short by his death, in which a robot with emotions longs to become a real boy. In an essentially negative review, published on July 2, 2001, in The New Yorker, film critic David Denby writes:

The story is based explicitly in "Pinocchio," but it gives us a queasy feeling from the beginning. Have the filmmakers forgotten that Pinocchio is a scamp? He's disobedient and lazy, he lies, he has a nose that rather famously gets longer. Pinocchio wants to be a real person because he's tired of being knocked around as a puppet. He is redeemed by love for his wood-carver "father" just at the very end of the tale (p. 87).I would wager that this fairly simplistic reading of Pinocchio is based more on memories of Disney's version than on the original tale, published first in serial form and then as a book in 1883. In Collodi's more complex story, there are many stimuli for "queasy feelings" as well as for other diverse emotional and intellectual responses, which careful readers, including prominent Italian and American authors, have experienced and used in order to shape Pinocchios of their own. Was the original Pinocchio merely a "scamp" who was simply "redeemed" by his putative father? Did he wish to be a real person only because "he was tired of being knocked around as a puppet?" I think not, nor do the many writers and filmmakers who have been inspired by the world's most persistent puppet. elberg's and Disney's films, but, first, I want to move into the twofold aim of this seminar: initially to detail the intricacies of Collodi's story, which is far from a simple children's tale about a "scamp"; then, to present several reworkings of Collodi in contemporary fiction and film that find in the story a rich fund of themes, motifs and images for exploring such still highly pertinent issues as the limits between the human and the non- (or post-) human, the toll of reaching responsible maturity and the place of education in that process, the function of transgression both for individuals and for society, and the ways in which dominant attitudes toward paternal and maternal roles have come historically and currently to have an essential impact on our collective concept of humanness. The beloved story of Pinocchio has not only entertained generations of children around the world (it is topped in worldwide sales only by the Bible); it has also provided fuel for many Italian (and other) writers of adult fiction and has been the inspiration for cinematic references that are instantly recognizable more than 100 years since Collodi first created the puppet. A contemporary archetype, the long-nosed, not quite human boy figure has entered into global popular culture (how many countless Pinocchio puppets, toys, statues, cartoons, references in ads and so on must there now exist?) as well as into literary high culture, most visibly in his homeland but also in the United States and elsewhere.My desire is to reveal just how rich and engaging a text the original book is (its specifically literary qualities, in other words), and then to analyze some of the appropriations of it; that is, I seek to consider its "use value," which certainly includes but also exceeds purely literary considerations and takes us into the realm of cultural criticism.

Pino Funnel. Designed by Stefano Giovannoni and

Mirriam Mirri for Alessi. Photo by Dan Dry.This funnel was designed for the Alessi Corporation, which is known for its whimsical and innovative kitchen implements. Versions of Pinocchio are to be found everywhere, as wooden toys, Murano glass statues, dolls, and the like, and there are numerous websites devoted to the puppet. SESSION 3: Pinocchio and Children's Literature

Few intimate details are known about the life of Pinocchio's creator, the lifelong bachelor Carlo Lorenzini, who was born in Florence on November 24, 1826, and who chose to take the pen name Collodi, the name of his mother's native town near Pescia in Tuscany. Collodi came of age as a writer in the "decennio di preparazione," the decade from 1850 to 1860, when Italy was moving toward unification. We do know that he, like many of his generation, was a participant in the1848-49 battles for Italian national independence and unity and that throughout the 1850s he was very active as a journalist, writing under a variety of names and on many topics, including politics and music.

from Carlo Collodi, lo spazio delle meraviglie Carlo Lorenzini or "Collodi"

Rebecca West In this slideshow, review the history of Collodi's publications that led up his most famous work, Pinocchio.

Collodi lived in a complex period of Italian history when there was a great push toward national unity but much ambivalence about what such unity would mean to a country deeply tied to local traditions, dialects and customs. The writer lived the new reality of a unified nation--a unification that he, a Republican against the Monarchists, had ostensibly supported--with true ambivalence. His beloved hometown, Florence, was the first capital of the newly formed nation for five years, for example, and Collodi disliked intensely the effect it had on a place that for him had previously been like "a great big house in which all the inhabitants knew one another." He was attracted by order, discipline and structured educational practices, but he was also fascinated by the occult, mesmerism and the inherent disorder of things.

There were many programs initiated after unification with the goal of "making the Italian people Italian," but in spite of his interest in pedagogical writing, Collodi was highly suspicious of them because he saw them as a threat to individuality and personal freedom. These clashes within Collodi find expression in his tale of Pinocchio, which it is possible to read as a tale of both transgression and the necessity for conformity.SESSION 4: Pinocchio and "Serious" Fiction

Pinocchio is considered to be a book for children: a common enough genre today, but a relatively new one in Collodi's time. Children's literature was an innovation in nineteenth-century Italy (and elsewhere). In fact, in Italian culture a strict division between adult and children's literature was for centuries quite an alien idea. Oral folk traditions and a strong classical education were very much a part of shared experience (the latter at least by those upper-class Italians privileged enough to have a formal education), and both young and adult Italians shared narratives that drew heavily on these sources.

European romanticism and children's literature The emergence of the category of children's literature in the nineteenth century is not confined to Italy, of course. European romanticism brought together an interest in children with a passion for popular literary forms and for mythic themes and structures.[more] The almost universal Catholicism of Italians also acquainted children with the Biblical events and figures that inform Italian lay literature. And because of the strength of the oral tradition, Italians were accustomed to the pleasures of a simple "good story" and unashamed of their enthusiasm for engaging and humorous tales, even if fairly simplistic ones. It was not until the nineteenth century, as nation building came to the fore and the formation of Italian citizens with shared values became a burning issue, that books written primarily or exclusively for children proliferated, acknowledging differences between the two readerships.

Pinocchio is a case in point. It relies heavily on the Tuscan novella or short-story tradition to which Boccaccio's Decameron belongs, and also on classical sources, such as Homer and Dante. As the critic Glauco Cambon wrote: "Storytelling is a folk art in the Tuscan countryside, and has been for centuries.... Pinocchio's relentless variety of narrative incident, its alertness to social types, its tongue-in-cheek wisdom are of a piece with that illustrious tradition" (p. 53). Further, Cambon highlights as well the importance of the Odyssey, the Aeneid, and the Divine Comedy to the structure and style of Pinocchio and concludes: "In a place like Italy, the cultural background would insure a deep response to this aspect of Collodi's myth, and guarantee its authenticity" (pp. 57-58). From its initial publication to today, the puppet's tale has been read and enjoyed by audiences of children and adults, both of which find different pleasures in it.

Sergio Strizzi Roberto Benigni in his self-directed Pinocchio. The contemporary Italian actor and director Roberto Benigni, whose humoremerges in great part out of the Tuscan tradition of the novella,especially out of the beffa, or trickster story, as well as out ofa very personal sort of bricolage of popular and high cultural references,has recently filmed his version of Pinocchio, starring himself asthe puppet; he had already been involved in the 1970s in a production ofPinocchio with filmmaker and playwright Giuseppe Bertolucci, thebrother of the more famous Bernardo, so his interest is quite long-standing.Benigni has commented (quoted online) that he is seeking to bring to thefore the Biblical elements of the tale ("a little child shall lead them"),and, given his great love for and knowledge of Dante, I would not be surprisedif Dantesque qualities will also be highlighted, as they were, along witha myriad of other "high" cultural referents, in Life is Beautifuland others of his films. I repeat that Pinocchio was in the past,as today, a tale that was immediately appreciated by adults as well as bychildren. This appeal to mature readers is evident currently in the waysin which filmmakers and "serious" writers continue to respond to it, eitherin indirect appropriations of some of its elements or in wholesale reworkingsof the puppet's story, as I shall discuss further on in some detail.

SESSION 5: The Blue Fairy and the Fantastic

Collodi's tale of Pinocchio may have fairy tale-like qualities that tie it to the genre of children's literature, but many of its elements are more allied to the tradition of adult, "serious" prose fiction. Its main personages, for example, have rather bad characters, unlike the unerringly good heroes and heroines of fairy tales. Pinocchio is transgressive and selfish for most of the tale; Geppetto is very hot-tempered; Ciliega (Mr. Cherry) drinks much too much; and the Blue Fairy is quite hard-hearted and often does not display much affection for the puppet. Moreover, the tale is set in a provincial Tuscany that was quite recognizable to readers when it first appeared, a world made up of everyday problems, among which was getting enough to eat. This is not at all the utopian world of typical fairy tales, in which material problems can be overcome by magic and everyone lives happily ever after.

Illustrations by Ugo Fleres for the serial publication of Pinocchio in the Giornale per i bambini, from the appendix to Perella's translated and annotated edition of the tale. In Ugo Fleres's first illustrations of the tale, which were published along with it in the Giornale per i bambini, we see how puppet-like Pinocchio is, in contrast to Disney's and other later conceptions, in which he is much more like a boy even before his transformation into a fully human being. Yet, as Italo Calvino noted, Pinocchio is "a model of narration, wherein each theme is presented and returns with exemplary rhythm and precision, every episode has a function and a necessity in the general design of the action, each character has a visible clarity and a linguistic specificity" (interview conducted by Maria Corti, in Autografo 2:6 [October 1985]); in this sense the tale follows, like the fairy tale or folk tale, a fundamental narrative prototype, as defined by Vladimir Propp. The dynamism of the action as it unfolds horizontally is much more important than deep psychological or extensive descriptive elements; the story itself is the thing, in short. As in many fairy tales, in Pinocchio too it is the overcoming of obstacles that pushes the tale forward, so that the hero or heroine may be rewarded with the happy ending.

In order to understand better the qualities that make of the puppet's tale something much more complex than a simple fairy tale-like story of goodness and obedience rewarded, however, it is first important to keep in mind that the book we now think of as a unified tale was in fact published serially under two titles over a three-year period. "La storia di un burattino" (The story of a puppet) was published over several months of 1881 in the Giornale per i bambini, a very popular children's magazine.

The first 15 chapters of the unified book are made up of these pieces, and in the last of them Pinocchio is hanged and dies. Collodi killed off his character evidently with no intent of resurrecting him, but the editor of the Giornale per i bambini pleaded with him to continue the very popular story, so in 1882 and into 1883 Collodi published piecemeal "Le avventure di Pinocchio," which became chapters 16 to 36 of the book.

from Pinocchio, 1883 Enrico Mazzanti, the illustrator of the first book edition of the entire tale, gives Pinocchio a slightly more human look, although he is still quite clearly a puppet and not a boy.

from Pinocchio, 1901 Illustration by Carlo Chiossi for the 1901 edition. There was further continuation of a sort in another serialized story called "Pipì o lo scimmottino color di rosa" (Pipi the little pink monkey), which Collodi published in the same children's magazine from 1883 to 1885, and in which there is a wealthy, obedient little boy named Alfredo, who seems to be the boy Pinocchio became after his transformation from wooden puppet to human being. It is not the good Alfredo who has been remembered and whose story has been endlessly retold, however, but rather the naughty willful Pinocchio who gets himself into one bad fix after another. In fact, in the first part of the book, "La storia di un burattino," there are scarcely any positive and educational elements, and the tale is more subversive than pedagogically correct. Only in the second part, "Le avventure di Pinocchio," does the puppet decide that he wants to become a "good boy," and this only in Chapter 25, closer to the end than the beginning of the tale. We all know that mischief and wrongdoing are much better spurs to dynamic narrative invention than stolid goodness, so it is not surprising that Collodi delays the puppet's conversion to goodness for much of his tale, in the service of what Calvino, in his Lezioni americane (Six Memos for the Next Millennium) calls the exemplary narrative qualities of "lightness" and "rapidity." The ethical quality of the story that has been much emphasized in its afterlife in popular culture, especially in the spectacular highlighting, by means of the growing nose, of the dangers of telling lies, is much less evident in Collodi's episodic creation, in which lying is just one of Pinocchio's many peccadilloes that include the common childhood "sins" of disobedience, loafing and skipping school.

SESSION 6: Rewriting Pinocchio

Sergio Strizzi Nicoletta Braschi and Roberto Benigni in his self-directed Pinocchio. One of the most significant additions to the second half of the book is the figure of the Blue Fairy, a civilizing female influence on the unruly puppet who had, up to her appearance, lived in an entirely masculine world of dog-eat-dog street smarts, macho bravado and dangerous trials and tribulations. The puppet's "birth" is accomplished without any maternal involvement, but his "rebirth" and eventual elevation to full human status take place under the sign of the mother, as if Collodi realized that a motherless creation is inevitably monstrous (à la Frankenstein) and doomed to exclusion from the human family.

In his very rich "An Essay on Pinocchio" that appears as the introduction to an annotated translation of the critical edition of the Italian book, Nicolas J. Perella discusses some of the complexities of the Blue Fairy, who first appears as a moribund little girl, a kind of sister to the puppet, and later, reborn, as a grownup, a kind of young mother. Perella sees her as having a "social bearing that lies somewhere between a lady of the middle class and a woman of the rural popular class." Her essentially bourgeois status is in decided contrast to the poverty-stricken status of Pinocchio's "father," Geppetto, who is most concerned about the "reality of hunger and a struggle to survive," and their socio-economic differences, according to Perella, mean that they could never live together as one happy family, just as, I would add, the Italians of Collodi's time were deeply divided along economic and class lines.

Discussion The mysterious Blue Fairy in Pinocchio offers fertile ground for scholars to debate her ambiguous role in the story.

Discuss the strengths or weaknesses of the various readings presented in this session (e.g., the Blue Fairy as symbol of class difference, Christianity, the female grotesque). Which reading do you feel holds the most merit, and why?Perella also notes that usually in the fairy tale tradition the mother or stepmother is the "crueler parent," while the fairy godmother is kind, but that the Blue Fairy, as an "internalized mother imago," is both benevolent and cruel, thus "blending the two concepts." There are many mysterious, even mythic aspects to this ambiguous figure, including her blue hair, her ability to metamorphose and her associations with death, and these aspects are among those that tend to fascinate some of the writers who have done their own versions of the tale. To use Mary Russo's phrase, the Blue Fairy is a "female grotesque," a being at once fascinating and repellent.

Given the dominant cultural referents in Italy, critics there have often associated her with the Virgin, who is traditionally depicted with a blue mantle, and have even read the tale as a Christological allegory, given that Pinocchio is the son of a carpenter whose name derives from Giuseppe or Joseph, and given also that the puppet must die in order to be reborn as a transfigured being. But, mother, sister, fairy godmother, or stand-in for the Virgin Mary, the Blue Fairy is a disquietingly rare female figure in a tale in which, as Perella writes, "the patriarchal family stands as an island of security in an egotistical, aggressively hostile world"--a patriarchal family, I might add, that is fairly much all patriarchy, and much less colored by the maternal than traditional families of the time would have been.

www.arttoday.com The Virgin Mary, as traditionally depicted wearing blue.

from Pinocchio, 1901 The Blue Fairy as depicted by Chiostri.

from Le avventure di Pinocchio, 1924 The Blue Fairy as drawn by Mary Augusta and Luigi Cavalieri. The Blue Fairy is not the only disquieting element in the puppet's tale. Pinocchio himself (or itself?) is mysterious from the beginning--first a piece of wood, but a very special piece of wood in that it speaks even before it is transformed into a puppet. The old carpenter mastr'Antonio, a tippler nicknamed Mister Cherry (Ciliegia) on account of "the tip of his nose, which was shiny and purplish like a ripe cherry," intends to turn the piece of wood into a table leg.

Mr. Cherry is stopped from cutting into the piece of wood by "una vocina sottile sottile" (a thin little voice) that pleads: "Don't hit me so hard!" Ciliegia thinks he is imagining the voice, and, although he is fearful, continues to manhandle the piece of wood very roughly, stopping only when, as he is planing the wood, the voice says, "Stop! You're tickling my belly!" Then the old man is so frightened that "the tip of his nose turned blue with fright." Violence, threatened mutilation and chilling fear permeate this rousing first chapter--just the stuff to hook young readers, and lots of fun for adult readers, too, who may be thinking that Mister Cherry has definitely had one too many.

from Pinocchio, 1901 Geppetto carries the piece of wood that will become Pinocchio, in this illustration by Chiostri. Ciliegia is only too happy to give his friend Geppetto the frightening piece of talking wood, and Geppetto, who had already declared his intention of carving a puppet "who can dance, and fence, and make daredevil leaps" (his goal is to travel the world with this puppet in order to earn his living), takes the wood home and begins to carve out his little future source of income. He names the puppet Pinocchio, which means "pinenut," and comments ironically that he once knew an entire family of Pinocchios who all did well for themselves, to wit, "the richest one of them begged for a living." Thus is the theme of hunger and of the constant search for enough food to survive introduced into the tale.

The mysterious pre-existence of Pinocchio, a sheer potentiality hidden in a piece of wood and waiting to be liberated into form, brings mythic elements into the story. As critic Rodolfo Tommasi has noted, in his reading of the symbolic and allegorical qualities of the tale, Collodi certainly would have been aware of Celtic and Nordic myths of talking trees that had been incorporated already into the French and Italian fairy tale traditions in writers such as Perrault and Luigi Capuana; moreover, Dante had provided a striking example of such magical vegetation in his Inferno, in the circle of the suicides who must suffer eternal pains as gnarled, speaking bushes and trees.

As Tommasi also notes, Geppetto's home is just the right sort of place between the real and the fantastic for such a birth to occur, since it is a humble abode with real, broken-down, meager furnishings but embellished with a painted fire and a painted kettle steaming away on the back wall. It is a liminal space, betwixt and between reality and fantasy, a "limen" or threshold on one side of which is potentiality and on the other, actualization. Pinocchio's potential existence, expressed in the little voice coming out of the unformed material, emerges in the form given by his creator, just as the formless soul is housed in the shape of a human body. (Dante's disquisition on the relation of the soul and the body in Purgatory [Canto 25] may have some relevance here.)

from Pinocchio, 1901 Pinocchio's hanging, a dark representation by Chiostri.

from Pinocchio, 1901 Night scene, illustrated by Chiostri.

from Pinocchio, 1901 Chiostri's depiction of the funeral. As the tale proceeds, more eerie elements are introduced: many gothic night scenes; Pinocchio's hanging; the funereal images that surround the dying little girl with blue hair. Yet the eeriness is balanced by the recognizably everyday characters and the open, cordial and "grandfatherly" tone of the narrator's voice, who recounts the amazing events in a very concrete and agile Florentine prose. The cordiality and sprightliness of the book's tone, the vivacious dynamism of the narration that carries Pinocchio ever onward through varied adventures, and the very ancient and recognizable themes of the voyage as initiation into maturity, the overcoming of hardships, and the search for a mother's love: all of these positive elements account for the book's mainstream appeal.

SESSION 7: Pinocchio in Film

Pinocchio's narrative verve and its darker and more transgressive qualities have appealed to numerous contemporary writers, among them, prominent Italian authors Gianni Celati, Umberto Eco, Luigi Malerba and Giorgio Manganelli, as well as the American writer Robert Coover. Filmmakers have also been attracted to the tale, and none so successfully as Walt Disney, whose 1940 animated version I shall consider in some detail. Before turning to Disney's film, however, I want to look at contemporary rewritings of Pinocchio. s, when Italian realist and neo-realist modes of narrative had exhausted their innovative potential and had become fixed in a mainstream type of linear narration and standardized style, experimental writers were looking for new and different models for the creation of prose fiction. An example of such experimental fiction is Gianni Celati's Le avventure di Guizzardi, published in 1973, which echoes in its title Collodi's book, Le avventure di Pinocchio. The similarity does not end there. Celati admired the picaresque and transgressive qualities of the puppet's adventures, and his book, although not at all an explicit rewriting of Collodi, also recounts the mostly negative adventures of young Guizzardi, who is kicked out of his home by his frustrated parents because of his unwillingness to work and settle down. The novel is highly episodic, as is Collodi's tale, and it is filled with menacing characters who use and abuse Guizzardi time and again. The choice of a children's book as implicit model was very significant, for it indicated a move away from high cultural models toward popular forms, a sort of return to storytelling as contrasted to the more dominant trend of realist novels that had come to define Italian prose fiction by the 1970s. Celati may also have been indirectly inspired by Calvino's first novel, Il sentiero ai nidi di ragno (The path to the nest of spiders), which was written shortly after the end of World War II, and which looked to Collodi's tale not only for the name of the boy protagonist, Pin, but also for the book's fairy tale-like, picaresque plot structure. Both Calvino and Celati, who ended up becoming close friends and sometime collaborators, often emulated the structural and thematic elements to be found in the tale tradition, whether written or oral, and Collodi's tale was a prime example of that tradition.

Already before the publication in 1973 of Celati's wonderfully inventive, Pinocchio-like tale, however, another Italian writer had revealed his fascination with Pinocchio in articles that appeared in the newspaper L'Espresso in 1968 and 1970. Giorgio Manganelli, who died in 1990, was one of contemporary Italy's most original writers. Deep into Jungian psychological models, a translator of Poe, the author of numerous books of extraordinary rhetorical complexity and thematic intensity (favorite themes include death, anguish and the dangers of love), and an expert critic of Baroque literature and of so-called minor writers of England and Italy, Manganelli was fascinated by the puppet child whose story held deep mythic and psychological resonance for him. He collected Pinocchio figures, and when I interviewed him in the mid-1980s at his apartment in Rome, I was amazed to see that his study was completely filled with large and small statues of the puppet.

After publishing his articles on Collodi's puppet in 1968 and 1970, Manganelli wrote a book called Pinocchio: un libro parallelo that appeared in 1978. At once a retelling of and a commentary on Collodi's tale, the book draws out the symbolic, allegorical and enigmatic qualities of the tale and concentrates much attention on the mysterious figure of the Blue Fairy, who is a bringer of both life and death: a seductive and dangerous female presence who is tied to the puppet as another being on the margins between the real and the unreal, power and abjection, conformity and transgression.

Pinocchio: un libro parallelo Book cover of Giorgio Manganelli's Pinocchio: un libro parallelo. In the newspaper pieces, which are now conveniently located in the 1986 collection of Manganelli's essays entitled Laboriose inezie, Manganelli writes of Pinocchio as representative of the ancient figure of the "trickster," who is present in many cultural traditions. He is solitary and must carry the weight of his transgressive role without being one with the society that assigns him that role. Manganelli further points out that the puppet's flight from home is also a journey toward something, and that "something" is his death as puppet trickster and rebirth as integrated human boy. Manganelli comments:

Killed by good actions, Pinocchio awakens as [in Collodi's words] "a boy like all others." ... That casual phrase touches the infantile dilemma: to accept both difference and uniqueness of self, or to lose both. Pinocchio gives up his uniqueness as a puppet; as a human he will have a name but he will be anonymous. As a puppet he was deformed, lacking in some sense, but let's not forget that his "deformity" was also a condition of freedom. ("La morte di Pinocchio," 314-15)There is no other twentieth-century Italian author who has meditated upon Pinocchio's meaning as deeply as Manganelli, nor are there many other modern authors who are as strongly on the side of difference, anomaly and uniqueness against the stifling and often death-dealing effects of conformity.

Pinocchio con gli stivali Book cover of Luigi Malerba's Pinocchio con gli stivali. Briefly I wish to consider two other contemporary Italian Pinocchios: Luigi Malerba's delightful Pinocchio con gli stivali (Pinocchio-in-boots) and Umberto Eco's "Povero Pinocchio!" (Poor Pinocchio), an entertaining linguistic exercise included in a collection of pieces of the same name. Malerba, another writer tied to the experimental school of the 1960s and 1970s, is a highly successful author of adult fiction, but he has also written many books aimed at young readers. His Pinocchio con gli stivali recounts the story of the puppet, who this time flees not from his home but from his own tale in order to hide in other famous fairy tales, motivated by his desire not to become a good little human boy. Pinocchio goes into the tales of Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, and Puss-in-Boots, trying in every case to get the characters to modify their stories and to include him. But they are all very conservative types and insist that what is written is written, although Pinocchio, rebel that he is, says that stories belong to everyone and can be changed according to how someone might wish to tell them. Malerba, like Celati and Manganelli, is clearly on the side of the transgressive puppet rather than the good little human boy; furthermore, he uses Pinocchio's crossing of story boundaries to say something important about the rules that govern storytelling and the ways in which those rules can be bent or broken in favor of inventiveness and originality.

Then there is Umberto Eco's "Povero Pinocchio!" which in fact was written by students in one of his seminars at the University of Bologna and re-elaborated by him. In this class, Eco had his students do a number of exercises in the form of linguistic games. The Pinocchio exercise was to write a summary of the tale in ten lines using only words beginning with the letter "P." Eco was so pleased with the results that he put together a number of the students' inventions into a longer piece. It is impossible, of course, to translate such a thing well, so I only give my attempt at translating a few excerpts into English:

Povero papà (Peppe),

palesemente provato/penuria,

prende prestito polveroso pezzo/pino poi,

perfettamente preparatolo/ progetta/prefabbricarne pagliaccettoPoor papa Peppe,

primarily penurially pinched,

picks paltry pine piece

perfectly prepared, projects puppet prefabrication.The exercise was to help students improve their vocabularies, but it also turned out to be a wonderful implicit commentary on the tale's meaning. With their suitable initial letter, the words "poverty" and "penury" are rightly highlighted in the students' versions; also, the "deus ex machina" function of the Blue Fairy is emphasized in phrases like "provvidenziale pulzella" (providential puppet), and the final lines are particularly witty: Paradossale! Possibile? Pupazzo prima, primate poi? Proteiforme pargoletto, perenne Peter Pan, proverbiale parabola pressoché psicoanalitica!

Discussion Following Umberto Eco's exercise, create a summary of the tale in ten lines using only words beginning with the letter "P." Post your version on the discussion board.

What themes are consistent with your classmates' summaries, and what new themes do you see emerging?

Paradoxical! Possible? Puppet, primate? Proteoform pest, perennial Peter Pan, proverbial parable practically psychoanalytical!Pinocchio's tale was one of the few stories that Eco could count on being known by all of his students, and his use of it shows how deeply it has penetrated into the collective consciousness of Italians, even if, as is so often the case with classics, many admitted to not ever having read the original book in its entirety.

Coover's "Pinocchio in Venice"

My last few comments regarding written versions of Pinocchio have to do with a fascinating novel by American writer Robert Coover entitled Pinocchio in Venice, which was published in 1991. Coover, who has won many accolades for his original, often experimental fiction, is the author of the well-known collection of stories Pricksongs and Descants and several other novels and story collections. Pinocchio in Venice is not only a postmodern tour de force, but it also reveals Coover's very deep knowledge of the original Italian tale, and of other aspects of Italian culture such as the Commedia dell'Arte, the history of Venice, and especially the Venetian carnival tradition. s a very old emeritus professor from an American university who returns to his native Venice in order to finish his magnum opus, a tribute to the Blue Fairy entitled Mamma. The aged Pinocchio relives all of his dangerous adventures as he slowly turns back into a wooden puppet. The book is raucous and bawdy, like a Commedia dell'Arte performance, but it is also a philosophical meditation in fictional form on what it means to be human.The choice to focus on the Blue Fairy as lost lover and mother is, I think, responsible in great part for the intensity of the book, which never strays for long from being an allegory of life as a voyage from maternal matrix or womb to dissolution or tomb. And the Blue Fairy, as in Manganelli's reading of her, is a powerfully protean figure, sometimes a silly, gum-chewing, big-breasted American girl named Bluebell, sometimes the lovely ethereal presence of the little girl with blue hair, sometimes a terrifying inhuman monster. All of her guises come together in her final meeting with Pinocchio who, on the verge of death, finally understands their bond as monsters, as beings excluded from full human existence, he as a piece of wood at heart, she as the lack that women have represented through the ages. It is a wonderful book, made even more enjoyable by a knowledge of the original tale's complexities that are animated once more in this thoroughly postmodern Pinocchio.

SESSION 8: Disney's Pinocchio

Many filmmakers have wanted to bring Collodi's tale to the screen, including Federico Fellini and Francis Ford Coppola. Neither ever did, although Fellini's final film, La voce della luna, starring Roberto Benigni, has overt allusions to the puppet's story. Other directors did make their versions of Pinocchio, whether in animation, with live actors, or a mix of the two, and there are at least 14 English-language films based on the tale, not to mention the Italian, French, Russian, German, Japanese and many other versions for the big screen and for television. Japanese anime cartoons owe a particular debt to Pinocchio, for Astroboy, one of the most popular figures of the genre, is based on the Italian puppet. Although Collodi did not provide a detailed description either of the appearance of his characters or of the settings, from its birth in serial form the tale has stimulated an extraordinarily rich illustrative tradition that in turn has nourished numerous cinematographic representations. Director and actor Roberto Benigni's film version of the tale, in which he will star as the puppet, is currently being awaited with great anticipation. In an interview given February 7, 2001, with the founding editor of La Repubblica, Eugenio Scalfari, which is now available on the newspaper's website, Benigni speaks with ecstatic enthusiasm about the project that has been a dream of his for many years. He did not read Collodi's tale until he was 20 years old, he says, nor could his parents have read it to him when he was a child because they were illiterate Tuscan peasants. But as a child Benigni was aware of the existence of the puppet nonetheless, because his mother would warn him that if he told lies his nose would grow like Pinocchio's and then Dante Alighieri would put him in Hell:

Then one day in the piazza I saw a statue of Dante, and with that nose of his I thought that he was Pinocchio. Later I found a sentence in the Convivio [a work by Dante] that says: "Truly I have been wood [a wooden boat] without direction, carried along by mournful poverty." Can you get more like Pinocchio than that?!With this humorous anecdote, Benigni makes clear just how strong a connection he perceives between the high-cultural reference par excellence--Dante--and Collodi's more humble but no less culturally important figure. The actor-director also comments on "how many beautiful things this puppet has caused to be written," mentioning the philosopher Benedetto Croce (who wrote that Pinocchio's essence is the "wood of humanity"), Calvino, Antonio Gramsci, writer-critic Pietro Citati, Marxist critic Alberto Asor Rosa and Giorgio Manganelli, the last of whom he calls "the funniest pinocchiologist of them all." Benigni's joy in working on his film version of the tale comes through very strongly in this interview, and his comments whet our appetite for the result of his long meditations on the beloved puppet. If anyone can succeed in bringing Pinocchio to full filmic life with accuracy and verve, it is this highly talented and sensitive fellow Tuscan, who is already known affectionately as "Pinocchio" for his antics on and off the screen.One of the most recent American productions of the tale is the1996 film The Adventures of Pinocchio, starring Martin Landau as Geppetto and Jonathan Taylor-Thomas as the "real boy" Pinocchio. The pre-human puppet in the mixed animated-live action sequences is the creation of Jim Henson's Creature Workshop (of Sesame Street fame). The New Adventures of Pinocchio, a sequel, was released in October 2001. The 1996 film follows Collodi's tale fairly closely, although there are some interesting changes. Set in a vaguely eighteenth-century Italy, with the villains often looking like Venetian carnival characters, from the very beginning the film is oriented much more to sentimentality than is Collodi's tale. As the film has it, years before the "birth" of Pinocchio, Geppetto had carved a heart enclosing his and his beloved Leona's initials into a tree in the forest, and it is that piece of wood that contains the magic puppet. Leona had married Geppetto's brother, and so Geppetto pined for her (pun intended!) for 25 years. Pinocchio is, therefore, their "love child," and we know from the start that they will all end up as one happy family.

The most obvious modification of Collodi's story is the absence of the Blue Fairy; instead we have the very human Leona (played by Geneviève Bujold), who is a potential mother for the puppet and nothing else. She is a sensible maternal presence, very unlike the mysterious and changeable Blue Fairy. Pinocchio, or "Woody" as he is called by his mischievous human friend Lampwick, learns in school that what separates humans from others is their ability to cry. This lesson comes to life just as Pinocchio does, for it is because of his tears that he is transformed into a real boy. The film is well-crafted but a bit plodding, and the European and American elements in it clash oddly. The talking cricket Pepe, for example, is very American in voice and manner, while the setting and the villains are all Old World. In spite of its shortcomings, however, it is a worthy adaptation to the screen of Collodi's tale.

SESSION 9: Futuristic (and Future) Pinocchios

In the English-speaking world at least, no filmmaker so far approaches the achievement of Walt Disney, who in 1940 released the animated version of Pinocchio that has continued for more than 60 years to condition our collective knowledge of and response to the puppet. Critics are in agreement about the technical splendors of the film, but it did not enjoy a strongly positive reception when it was first released, and there are still today very differing readings of it. The cover of the sixtieth anniversary edition of the video tells us that it is Disney's "immortal masterpiece" and quotes TV Guide's assessment of it as "arguably the greatest animated feature of all time!" Disney's 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs had already achieved a huge advancement in animation; Russian director Sergei Eisenstein called it the greatest film ever made, for it showed that cartoons could represent any visuals a director might conceive of, thus creating a vast new realm of cinematic creativity and freedom.ng with Fantasia, built on the achievements of Snow White and the collaboration of hundreds of artists and technicians brought together in a kind of "collective creative epiphany," to use Chicago film critic Roger Ebert's words. Ebert provides good information about the specific technical innovations of Disney's film: for one, the breaking of the frame, by means of which it is implied that there is space outside the screen, a technique of "regular" live-action films not used in animation until Disney's people made it possible. Thus in the exciting sequence in which Pinocchio and Geppetto are expelled by the whale Monstro's sneeze, then drawn back in, and then again expelled, there is a palpable sense of the presence of the whale offscreen to the right. Audiences are probably much more taken with the wonderful score, the strikingly human-like characters (with perfectly chosen voices), and the allusions to recognizable types from high as well as popular culture than with the film's technical innovations, which they may or may not notice. As for its music, we remember that the film won Oscars for Best Original Score and Best Song, the unforgettable "When You Wish Upon a Star." And, as for characters: by paring down the large cast of characters in the original book to a few well-drawn (in all senses of the word) good and bad types--the kindly Geppetto, the adorable innocent Pinocchio, the All-American hayseed Jiminy Cricket, the luscious Blue Fairy, Geppetto's darling, very humanized pet cat Figaro and flirty pet fish Cleo, pitted against the rapacious fox Little John, the gross puppetmaster Stromboli, the sadistic Dickensian Foulfellow, the terrifying whale Monstro--Disney offers a genuine morality tale in which Good triumphs over Evil, according to the fairly saccharine code expressed primarily by the Blue Fairy: "Prove yourself brave, useful and truthful"; "A body who won't be good may just as well be made of wood"; "Give a bad boy enough room and he'll soon make a jackass of himself"; "When you wish upon a star, makes no difference who you are," and so on. It may be that children continue to enjoy the film because, as film critic Roger Ebert states, "all children want to become real and doubt they can," so that they identify strongly with Pinocchio's wish to become a real boy. (I quote from the Web page of the Chicago Sun-Times; however, Ebert's essay on Disney's Pinocchio is now available in his 2002 book, The Great Movies.)

Or, I would suggest that it may be that young viewers respond most to the film's deeply frightening aspects that have something of the primal about them, as do classical fairy tales that enthrall kids over and over. I myself remember being haunted for a very long time by the wicked stepmother and the horrible witch of Snow White, and by the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz. I did not "identify with" Snow White or Dorothy, though; in fact I wanted to be a witch, and I now think that what I really wanted was her power over others and her deliciously transgressive way of life. It may be that something like this attraction to the transgressive pulls children into Pinocchio's story, not because they want him or themselves to be "real," but because they relish his brushes with danger and death, vicariously thrilling to experiences that are otherwise out of their reach.

Discussion Do you feel that it is the transgressive or dark nature of the fairy tales, such as Pinocchio, that keep the stories current? In a richly informative book containing marvelous illustrations, Walt Disney and Europe: European Influences on the Animated Feature Films of Walt Disney, author Robin Allan describes the less than sunny aspects of Disney's Pinocchio in a chapter called, appropriately enough, "The Dark World of Pinocchio." Although I think that Allan is wrong when he calls Collodi's book a work of "homiletic Victorian values," he is right on the mark when he writes that "the darkness of [a complex and frightening] world forms the central bleakness of the film and this is, for all its adaptation, the strongest link between Disney and Collodi" (p. 73). By "all its adaptation," Allan is referring to the ways in which Collodi's story had already been mediated by earlier bowdlerlized versions of the book (alterations and adaptations that had, over the years, shortened the tale and often removed some of its darker episodes), versions that in turn had provided the basis for a play by Yasha Frank that was performed in Los Angeles in 1937 and subsequently published in 1939. Frank's Pinocchio was an innocent, incapable of promoting mischief, unlike Collodi's puppet, who has a seemingly natural attraction to transgressive and delinquent behavior.

Disney followed adaptations much more than the original, as he modified the sadism and violence in order to bring to the screen a lovable, cuddly Pinocchio. Nonetheless, as Allan writes, "the film is dark in content and in presentation, with 76 of its 88 minutes taking place at night or under water" (p. 67). The Disney movie is an odd blend of its European origin and American elements--in the latter case, the most important of which is the Will Rogers-type hobo, Jiminy Cricket--and its Old World cultural referents dominate the ultimately unsuccessful Americanization of the tale: for example, Commedia dell'Arte characters upon which the Fox and his stupid sidekick Cat are based; the Dickensian Foulfellow who shanghais Pinocchio to Pleasure Island; and the setting itself, which has the look of a Bavarian or Austrian Alpine village, the result of the work of Swedish artist Gustaf Tenngren who came to the Disney studios a few years before the film was made.

One of the most disturbing Old World characterizations in Disney's film is that of the greedy puppetmaster Stromboli, who is quite obviously portrayed as a Jewish gypsy, in spite of his stereotypically broad Italian accent. Collodi's puppetmaster Mangiafuoco "seems a fearful man but deep down he isn't bad," nor does he have any sort of marked ethnic or racial identity. From an anti-Semitic perspective, Stromboli's gross facial features and his long black beard are recognizably Jewish, as is his excessive love of wealth. Critic William Paul has suggested that Stromboli is "a burlesque of a Hollywood boss.... Disney's own relationship to the Hollywood power structure was always a difficult one" (quoted in Allan, p. 87). Richard Schickel was the first critic to bring a clear charge of anti-Semitism to the film in his 1968 book Walt Disney, although some of Disney's closest colleagues were Jewish and insisted that they were unaware of any prejudice on his part. Stromboli does disturb a viewer today, however, for it is simply impossible to ignore the anti-Semitic implications of his characterization. And it is all the more disturbing when one thinks of the period in which the film was made and the anti-Semitism that was being spread like a plague in Europe by Hitler's Nazi Reich. g" (to return to critic David Denby's comment), if much less deeply disturbing, characterization is that of Disney's Blue Fairy. Like the few other female presences in the film--Cleo, Geppetto's flirty, long-lashed fish, or the dancing girl puppets in Stromboli's Marionette Theater, who wear various national costumes as if they are contestants in a Miss World beauty pageant--the Blue Fairy is an utterly stereotypical feminine figure whose role, although ostensibly central in making Pinocchio come to life as a puppet and again as a real boy, is actually quite marginal in terms of actual screen time and impact. Completely antithetical to Collodi's deeply mysterious and manipulative Blue Fairy, Disney's is a 1930's "glamour girl" who is a solid, shapely human presence rather than an ethereal apparition. She is a "deus ex machina" who enters the scene early on to grant "good Geppetto" his wish made upon a star that the puppet become "real." She utters the magic words "Little puppet wake, the gift of life is thine," and the already humanoid and very cuddly puppet Pinocchio begins to move and talk, thus completely eliding the line between the human and non-human, unlike Collodi's tale in which Pinocchio's emergence from a talking piece of wood emphasizes his non-human status (as do the earliest illustrations to the book). Nor does Disney's Fairy function in any sense as a mother figure; she certainly does not look motherly at all, but has the appearance more like that of a Hollywood starlet. Her sole function in Disney's version is as a magic presence that can get Pinocchio out of apparently hopeless fixes; this means that she flits in and out of the film with no deeper resonance than an inanimate magic wand or potion would have. Her single goal is to get Pinocchio to be a good, obedient boy, back in the warm protection of Geppetto's fatherly space, where mothers are simply not needed, just as femaleness in any form (Cleo the fish, the seductive marionettes) is shown to be primarily decorative, the equivalent of the dumb blond or "bimbo" of Hollywood manufacture.

Discussion Cartoons often preserve the racial and gendered stereotypes (e.g., bloodthirsty Indians, bumbling Japanese soldiers, lazy Mexicans) of the period in which they were made.

Should such cartoons be censored today, and would you make the same recommendation for works of literature?If my comments on Disney's Pinocchio seem to be primarily negative, I wish to temper that impression by stating that in fact I find the film to be a remarkable technical achievement and a truly fascinating work. It is not only highly engaging and entertaining; it is also a rich cultural document, due mainly to its "hidden" or subtextual elements that reveal, perhaps unwittingly, artistic and social models, prejudices and stereotypes of the period in which it was made that were both collective, and specific to Disney. (This, I think, is also the case with Collodi's tale, indeed with any work that resonates more deeply than lesser works of merely superficial appeal.) If the subtexts generated by Stromboli and the Blue Fairy suggest the negative Jewish and female models that had thoroughly permeated American culture and society by the era in which Disney was making his film (the late 1930s), there is, on the other hand, an element introduced very early on in the film that I find charmingly yet not at all simplistically positive. It is one that in fact transcends historical and cultural prejudices and reaches into the heart of artistic creativity.

Just as some literary works are metaliterary--that is, they contain writing about writing itself, and about their own themes and structures--so too films can be and often are metafilmic. A famous example is Fellini's Otto e mezzo, in which a director is trying to make a film that ends up being the film we are watching. Animated features are not often thought of as metafilmic, yet Disney's Pinocchio is just that. It is an animated film in which the main character is precisely a non-human who is animated, thus becoming a simulated "human." This theme is highlighted very strikingly in the lengthy sequences in Geppetto's cottage that focus on the numerous clocks and toys that he has carved, which all depict simulated human animation, thus crossing the boundary between the human and the non-human. In Geppetto's workshop we see what is in effect a pre-filmic world of animation in which little carved mechanical figures are made to move, just as drawn figures will be made to move on the screen.

The anthropomorphic characterizations of animals--Figaro the cat, Cleo the fish, the Fox and, first and foremost, Jiminy Cricket--represent another crossing of lines, this time between the animal or insect and the human. Puppetry, the dominant technique of animation inscribed into the story, is, of course, embodied in Pinocchio himself, but in addition we have Stromboli's marionettes, which function as another layer of self-conscious commentary on the animation of objects in human form.

With Pinocchio, Disney and his team of dedicated artists were not only creating simulated humans on screen, they were also revealing something of the fascination that such animation exercises perhaps as much on its creators as on those who enjoy the fruits of their labors. However, there is a dark side to this urge to create life (even if only simulated life). Geppetto is the version in bono of the artist as benevolent God; there are no more charming scenes than those in which his many humanoid creations come to life, or those in which we witness his delight in his "son," Pinocchio, even before the puppet has been given independent voice and movement by the Blue Fairy. Stromboli is the version in malo, however. He is the evil puppetmaster God who creates the illusion of life only for personal gain and glory. The ancient theme of the dangers of hubristic creativity hovers around this film, but there is also inscribed into it the sheer joy of creation that seeks to animate lifeless things and to endow all objects and animals with such "human" qualities as the capacity to love and to live with conscious pleasure and direction.

ABOUT THE AUTHORRebecca West Rebecca West is professor of Italian in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and professor in the Committee on Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. She is also the director of the Center for Gender Studies. West is the author of Eugenio Montale: Poet on the Edge (Harvard University Press, 1981), Gianni Celati: The Craft of Everyday Storytelling (University of Toronto Press, 2000) and is co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to Modern Italian Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2001). COPYRIGHT Copyright 2002 the University of Chicago.

The fascinating question of what constitutes the boundary between humans and non- or post-humans informs Spielberg's 2001 film, A.I: Artificial Intelligence. At the beginning of this essay I quoted from the review by David Denby in The New Yorker in which the critic does not have many good things to say about the film. Other review articles, in the British film magazine Sight and Sound and in The New York Review of Books, are more positive and bring out issues that are tied to some of those that I have discussed in my consideration of Pinocchio. In addition to the explicit references to the tale of Pinocchio in the film--the human mother reads the puppet's story to her robot or "mecha" son, who then decides he wants to be human and, upon his expulsion from the home, has a series of Pinocchio-like negative adventures as he searches for the Blue Fairy--it is possible to read the film, like Disney's Pinocchio, as another "metafilm."

Geoffrey O'Brien highlights this aspect of the film in his August 9, 2001, New York Review of Books article "Very Special Effects," where he writes: "A.I. is a meditation on its own components; the technical means that make possible the mechanical child are as one with the means used to make the film.... Now that we have the technology what are we going to use it for?" (p. 13). This "technology" of creation generates some of the same ethical and philosophical concerns that now whirl around the advances in science that permit babies to be created in test tubes and animals to be cloned.

In the original Collodi tale, in Disney's film, and in A.I., the puppet (or robot) is created by Godlike fathers as a child figure intended to serve the needs, material or emotional as they may be, of the parent. Collodi's Geppetto wants his puppet to help him make a living, Disney's Geppetto wants his puppet to give him companionship and love, and Spielberg's mecha, David, is created specifically and uniquely in order to love his human parents unconditionally. Geppetto is a craftsman, allied to the tradition of poeisis or creativity to which artists belong, while the mecha's creator, Dr. Hobby, is a scientist (although a "poetic" one who wants to make a robot who can "chase down his dreams"). Nonetheless, they are, artists or scientists, all figures of the male creator who appropriates the procreativity of the maternal realm as they singlehandedly "give birth to" their "sons," effectively excluding women from their worlds except in highly idealized and symbolic, rather than active, roles.

Discussion Consider Rebecca West's proposition that in Spielberg's A.I., Collodi's Pinocchio and Disney's Pinocchio male figures desire the ability to procreate. In these narratives, discuss the role of woman as mother figure.

How do the reactions of the creations to their creators differ?In A.I., when an associate of the apparently benign designer of mechas, Professor Hobby (a Geppetto stand-in), makes what critic J. Hoberman calls "an obscure moral objection" to Hobby's creation of "a robot child with a love that will never end," Hobby's reply is "Didn't God create Adam to love him?" Hoberman comments, "Yes, of course, and look what happened to him" (p. 17). In fact, the mecha David is also expelled from Eden, and he futilely looks for the fictional character Blue Fairy to make him a "real boy" so that his mother will want him back. Eden regained is an impossible goal, however, and the most David can have is one perfect day with a reconstituted simulacrum of his mother.

Conclusion

In my reading of Collodi's tale and its many "heirs" in subsequent fictional and filmic works, I have sought to bring out elements that make of the story of Pinocchio much more than a simplistic lesson in the importance of obedience and conformity. The ever valid question of how and to what end human beings are created and shaped is rendered even more complex by a consideration of the role of the feminine symbolic as it complicates what is and remains in most cultures and most eras a fundamentally patriarchal view of creation.

Sergio StrizziNicoletta Braschi in Roberto Benigni's Pinocchio. I believe that it is not insignificant that the most anodyne reworkings of Pinocchio elide the complex figure of the Blue Fairy, while the more thought-provoking uses of the tale (as seen in Manganelli's work, or Spielberg's film) highlight the female principle in a worldview that is nonetheless still fundamentally patriarchal, be it the nineteenth-century Italy of Collodi or the futuristic West of Spielberg (and of Kubrick, of course). Human creativity, whether an art, a craft, or a technology, can yield astounding results, but the power to bring into being real or simulated versions of ourselves is fraught with dangers, not the least of which is the illusion of total control over the creatures we make. The anomalous, the abject, or the sheer excess of individual desire--all historically associated with the feminine sphere--cannot be tamed or repressed merely by admonishments to conform to the Law of the Father, to be "good little boys." So, happily, Pinocchio goes on fleeing his destiny as a "good boy like all the others" until, sadly, that destiny catches up with him. Collodi enlisted the aid of the feminine in the taming of the puppet, but it is worth remembering that, at the end of the tale, the Blue Fairy only appears in a dream to Pinocchio, as the perfect mother he would wish her to be. What or who in fact she may truly be or truly desire is known only to her.

Similarly, the mecha David is "reunited" briefly with the mother of his dreams at the end of A.I., but neither she nor he is real, and their "perfect day" of mother-son bonding is disturbingly hollow. Pinocchio's and David's "dreams come true," as Disney's Jiminy Cricket so movingly sings, but at what price? Who put these dreams of perfect goodness and filial bonding into their heads? In reality, boys' dreams of idealized mother figures might be comforting to them, but the dreams of their fathers or father figures who are avid for total control of their sons--effectively the motherless puppets that male children so often are in societies and cultures in which the feminine symbolic is radically marginalized--can be, if realized, our worst nightmares come to life.

(c) 2004 The University

of Chicago :: Please direct questions

or comments to furlong@lib.uchicago.edu |